Back in the early-1990s, when I was in college, in Lucknow, I had a Yamaha RX100 as my daily

runabout and I absolutely loved that bike. Small, light and revvy, my RX was

always raring to go. On the street, it would make mincemeat of Yezdi 250s, Kawasaki-Bajaj

KBs and assorted TVS-Suzukis. The RX would explode off the line, wheelie

endlessly and scrape its footpegs in fast corners even as its skinny tyres scrabbled

for grip. Only the mighty Yamaha RD350, which was thrice as powerful as the RX,

could bring the latter to its knees. But there was actually one more bike at

that time, which wasn’t very popular and which was in production only for a

very short time, which could occasionally keep up with the RX100. And that bike

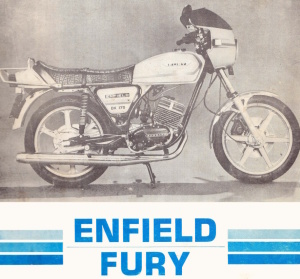

was the Enfield Fury 175, which was essentially just a rebadged Zundapp KS175

of East German origin.

In 1987, Enfield (now Royal Enfield) needed something to take on the

Indo-Japanese 100cc motorcycle brigade that had descended upon India, and their

age-old Bullet 350 simply wasn’t up to the task. And hence Enfield entered into

a tie-up with East German Zundapp, with whom they brought three bikes to India –

the Explorer, the Silver Plus and the Fury. The first two had a 50cc engine,

while the Fury got a 163cc two-stroke single-cylinder unit that produced 15.5

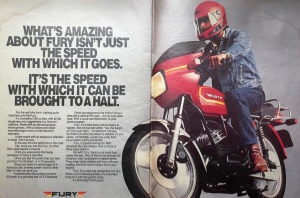

horsepower. The official tagline for the Fury 175 was ‘Choose the bike with the

quick pick-up. Not the fast pack up.’ Enfield insisted that ‘once you ride the

Fury, no other bike really stands a chance,’ though customers probably did not

agree and the bike failed to do well in India. The reasons for that could be

manifold – the Indian motorcycle market at that time was more about

fuel-efficiency than anything else, and Hero Honda ruled the roost with its 80kpl

CD100. Also, the Enfield dealership network at that time probably wasn’t

equipped to service and maintain something like the Fury, which was a major

departure from the Bullet 350 that they had been servicing for decades. And the

bike itself had its niggles – the Fury’s 5-speed gearbox wasn’t all that great

and the rider had to deal with multiple false neutrals while changing gears.

However, when it did run and when the rider could avoid getting a false neutral

while upshifting under hard acceleration, the Fury 175 could outpace the RX100,

given that the latter was almost 5bhp down on the former.

Zundapp, along with other legendary motorcycle brands of German / East German origin (for example: Sachs, Kreidler, MZ, Horex, NSU, Munch and DKW), used to make good, reliable motorcycles up until the 1970s-80s, but fell upon hard times when it could not match up to the Japanese competition that kept intensifying over the years. The company shut shop in 1984 but its bikes were still quite suitable for India, which in the 1980s was still stuck in the stone age of motorcycling. That the Explorer, Silvery Plus and Fury could not do well here was more of a marketing and aftersales/service failure on Enfield’s part more than anything else – the company, back then, simply wasn’t equipped to produce and sell anything other than the Bullet 350, which it had been selling for decades.

When I was working with BIKE India, in Pune, back in the mid-2000s, I happened to ride a Fury 175 for a story that I did for the magazine. The bike belonged to one Satish Apte, a committed motorcycle enthusiast, ex-racer and proud owner of a reasonably well-maintained 1987-model Fury DX175. Satish and I met early in the morning on a newly-constructed stretch of the highway and he handed over the keys to me. The two-decade old Fury started on the first prod of the kickstarter, which is positioned on the left-hand side of the bike. The engine emitted the same two-stroke snarl that I remembered from my college days, when one could occasionally spot one of these bikes in Lucknow. Satish’s bike also had lots of smoke coming out from the long-ish exhaust pipe, another characteristic I remembered from the 1990s. The bike had been raced in the past and had done God knows how many thousands of kilometers over the years, but the engine sounded all right. The bike accelerated cleanly, going up through its notchy five-speed gearbox and ultimately reaching a speed of around 90kph. To be honest, the gearbox felt terrible, with the shift lever traveling a long way before actually finding a cog – it was a far cry from the smooth click-click action of modern Japanese and European bikes. But Fury owners had learned to live with the gearbox issue and on that day, I enjoyed riding the bike – a rolling piece of history – despite the notchy gearbox.

On the road, the Fury felt very light and manageable. Given its age, suspension and braking components had taken a beating on Satish’s bike – the rear shocks were sagging, the non-ventilated disc brake at the front felt wooden and remote, and the ancient tyres weren’t very confidence-inspiring to say the least. But looking at the levers, the front forks (that were still firm after all those years!) and the alloy wheels, one could imagine that this would have been a high-quality piece of kit when it was brand-new. I tried to imagine how Fury 175 riders might have felt when they took delivery of their new bikes in the 1980s. At that time, a carefully-ridden Fury would have had the power to smoke all punters on their 100cc Indo-Jap machines, as well as Yezdis and Bullets etc. For me, riding the Fury was just a trip down memory lane, but for owners who bought these bikes when they were new, in the 1980s, the Fury 175 would have been great fun to ride, I’m sure.

Today, I suppose very few Enfield Fury 175s would still be in running condition. Most of these bikes would have rusted away long ago and would have been consigned to the scrap yard. Some have been restored, others live on in their owners’ memories. As for me, I’m happy I got an opportunity to at least ride a Fury 175 once and see what Zundapp was all about. After riding the Fury, I wish Zundapp were still around and still producing motorcycles. If wishes were horses...

Zundapp, along with other legendary motorcycle brands of German / East German origin (for example: Sachs, Kreidler, MZ, Horex, NSU, Munch and DKW), used to make good, reliable motorcycles up until the 1970s-80s, but fell upon hard times when it could not match up to the Japanese competition that kept intensifying over the years. The company shut shop in 1984 but its bikes were still quite suitable for India, which in the 1980s was still stuck in the stone age of motorcycling. That the Explorer, Silvery Plus and Fury could not do well here was more of a marketing and aftersales/service failure on Enfield’s part more than anything else – the company, back then, simply wasn’t equipped to produce and sell anything other than the Bullet 350, which it had been selling for decades.

When I was working with BIKE India, in Pune, back in the mid-2000s, I happened to ride a Fury 175 for a story that I did for the magazine. The bike belonged to one Satish Apte, a committed motorcycle enthusiast, ex-racer and proud owner of a reasonably well-maintained 1987-model Fury DX175. Satish and I met early in the morning on a newly-constructed stretch of the highway and he handed over the keys to me. The two-decade old Fury started on the first prod of the kickstarter, which is positioned on the left-hand side of the bike. The engine emitted the same two-stroke snarl that I remembered from my college days, when one could occasionally spot one of these bikes in Lucknow. Satish’s bike also had lots of smoke coming out from the long-ish exhaust pipe, another characteristic I remembered from the 1990s. The bike had been raced in the past and had done God knows how many thousands of kilometers over the years, but the engine sounded all right. The bike accelerated cleanly, going up through its notchy five-speed gearbox and ultimately reaching a speed of around 90kph. To be honest, the gearbox felt terrible, with the shift lever traveling a long way before actually finding a cog – it was a far cry from the smooth click-click action of modern Japanese and European bikes. But Fury owners had learned to live with the gearbox issue and on that day, I enjoyed riding the bike – a rolling piece of history – despite the notchy gearbox.

On the road, the Fury felt very light and manageable. Given its age, suspension and braking components had taken a beating on Satish’s bike – the rear shocks were sagging, the non-ventilated disc brake at the front felt wooden and remote, and the ancient tyres weren’t very confidence-inspiring to say the least. But looking at the levers, the front forks (that were still firm after all those years!) and the alloy wheels, one could imagine that this would have been a high-quality piece of kit when it was brand-new. I tried to imagine how Fury 175 riders might have felt when they took delivery of their new bikes in the 1980s. At that time, a carefully-ridden Fury would have had the power to smoke all punters on their 100cc Indo-Jap machines, as well as Yezdis and Bullets etc. For me, riding the Fury was just a trip down memory lane, but for owners who bought these bikes when they were new, in the 1980s, the Fury 175 would have been great fun to ride, I’m sure.

Today, I suppose very few Enfield Fury 175s would still be in running condition. Most of these bikes would have rusted away long ago and would have been consigned to the scrap yard. Some have been restored, others live on in their owners’ memories. As for me, I’m happy I got an opportunity to at least ride a Fury 175 once and see what Zundapp was all about. After riding the Fury, I wish Zundapp were still around and still producing motorcycles. If wishes were horses...

No comments:

Post a Comment